Yesterday, I was invited to deliver a keynote speech at Frankfort’s Liberty Hall Historic Site (what a history, there!) to kick off their celebration of Civics Season. They asked me if I would be willing to talk about my work on Driftwood, and here is the result of my, admittedly, challenging thought experiment of connecting the Hubbard story to civic engagement:

“Thank you so much for having me with you today, at beautiful Liberty Hall, to kick off Civic Season and celebrate the rich culture and history of our Commonwealth and its diverse communities!

When I was invited to be here to discuss my recent research and writing on the artist, writer, and sustainability pioneer Harlan Hubbard, I was excited by the challenge of connecting his legacy to the traditional idea of civic engagement. After all, one of his books is quite literally subtitled “Life on the Fringe of Society”—which is, admittedly, not a phrase that encourages one to think of Harlan as a model for citizenship. And, indeed, it would be safe to say that Harlan was a-political—at least in the most prominent ways we think of being “politically engaged” in America today.

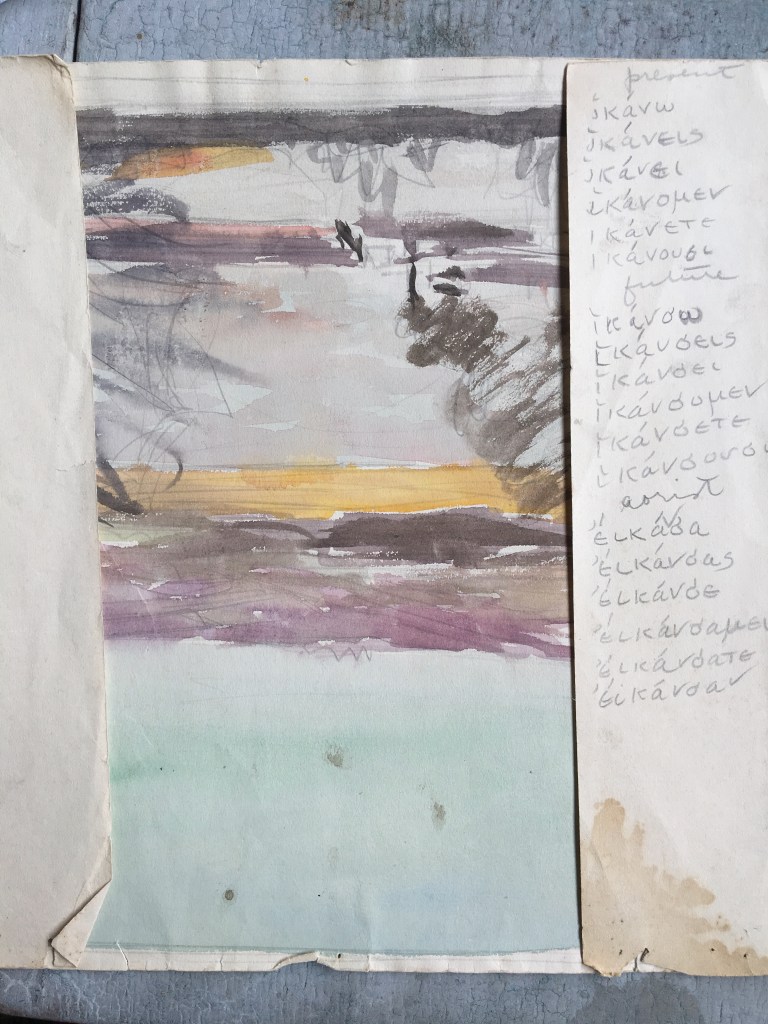

But as I considered how I might frame the idea of civics within the Hubbard story, I found myself looking at one of Harlan’s paintings I have in my personal collection. It is a very simple watercolor sketch of a barge passing on the river, made from the lofty vantage of Harlan’s 1920s studio in the Northern Kentucky hills along the Ohio. At some point, Harlan repurposed the sketch for some notetaking, and the spaces beside the painting contain some practice Harlan was making in writing Greek. In addition to being fluent in both French and German, Harlan made great study of both Greek and Latin, taking lifelong pleasure in reading and translating classics: Pliny, Ovid, Virgil, Homer.

Harlan’s interest in classical Western literature extended to knowledge of and interest in its history. Perhaps he had read or studied the famous speech of the Greek statesman Pericles—the Funeral Oration—in which the orator says of the citizens of Athens:

“The freedom we enjoy in our government extends also to our ordinary life. There, far from exercising a jealous surveillance over each other, we do not feel called upon to be angry with our neighbor for doing what he likes. […] At Athens we live exactly as we please, and yet are just as ready to encounter every legitimate danger.”

Pericles stresses, in his speech, that a government that makes room for all kinds of lives, skills, and expressions of citizenship is stronger—not weaker—than one which demands obedience. This, to me, is a kind of civics Harlan could have gotten behind: civics that is squarely centered in personal responsibility to the community but also acknowledges that happy communities are made up of humans who have been encouraged to live into those personal responsibilities in their own, unique, ways.

But, I’m getting ahead of myself. First, I need to share with you—for those of you who don’t already know—a little context about why it should matter to you what Harlan Hubbard thought about civic responsibility. Harlan Hubbard and his wife, Anna—as a writer for your Lexington Herald-Leader so eloquently put it—are “the most famous Kentuckians you’ve never heard of.” I laughed out loud when I read that, because it has been my experience, while working on my recent biography of Harlan, that people were either religiously devoted to the Hubbard legacy or knew exactly nothing about who they were. Until recently, there was rarely a middle ground. That is changing somewhat, these days, as the Hubbard story gains broader recognition.

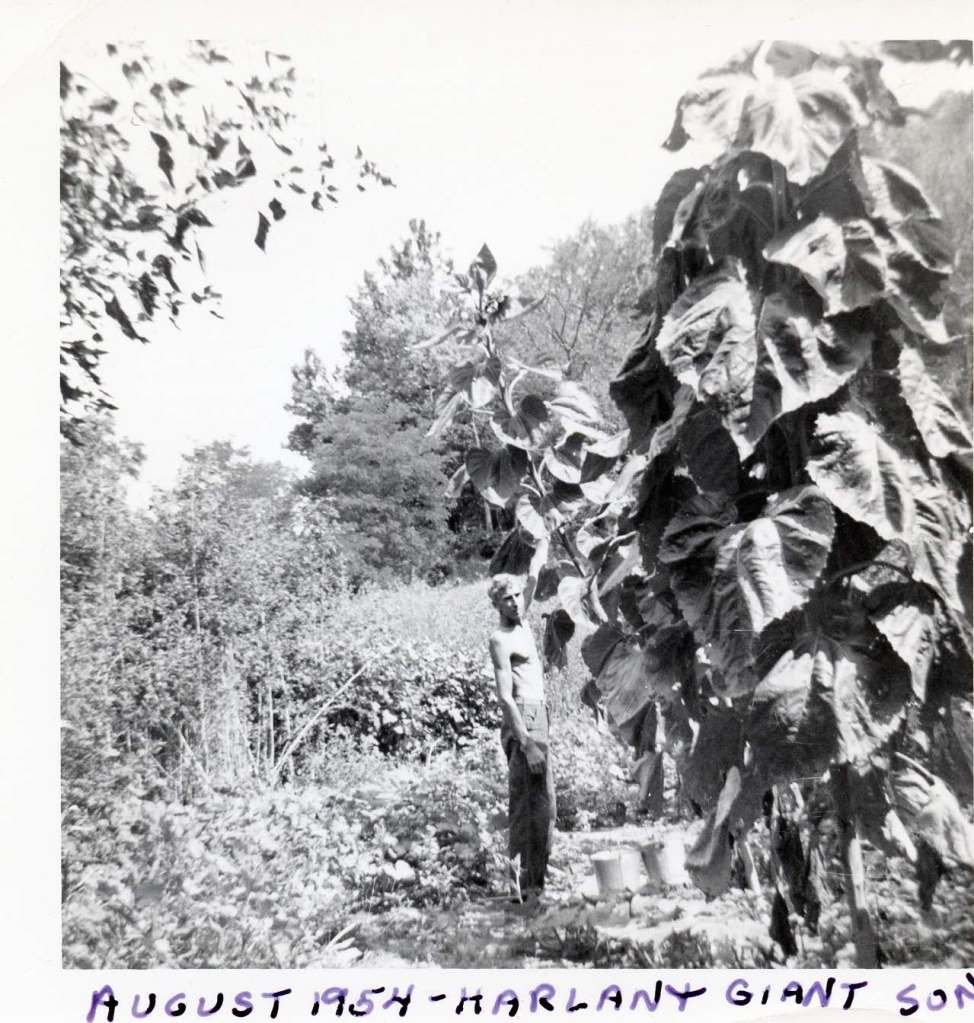

If you happen to have heard of the Hubbards already, here is probably what you know: that Harlan and his wife, Anna, took a scintillating adventure on a hand-built shantyboat down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in the 1940s and then, in the 1950s, settled at a place called Payne Hollow, in Trimble County, Kentucky, where they lived without electricity or indoor plumbing—growing, foraging, bartering, or fishing for everything they needed. This should serve as a basic introduction for you to the Hubbards as countercultural figures in Kentucky history—and give a little insight as to why the idea of the Hubbards as models for traditional civic engagement was giving me a bit of a struggle.

The Hubbards’ experience as shantyboaters—and commitment to the “shantyboater ethos”—is foundational to their countercultural impulse. In his breakout book, Shantyboat, published in 1953 about their adventure on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, Harlan writes:

“A true shantyboater has a purer love for the river than had his drifting flatboat predecessors. These were concerned with trade or new land. To him the river is more than a means of livelihood. It is a way of life, the only one he knows which answers his innate longing to be untrammeled and independent, to live on the fringe of society, almost beyond the law, beyond taxes and ownership of property.”

Later, in his 1974 book I mentioned earlier, Payne Hollow: Life on the Fringe of Society, Harlan says:

“Shantyboating has become a point of view, a way of looking at the world and at life. You take neither of them too seriously, nor do you try to understand their complexities. Who can? It is an obviously illogical philosophy, in which the individual is supreme. The claims made on him by his inner beliefs are above the demands of society. He is not without compassion, but his love is expended on those of his fellow men he is in contact with. With no schemes for universal betterment, he tends his own garden.”

That last phrase, is, of course, a reference to another countercultural revolutionary Harlan loved, Voltaire, whose comment in his novel Candide, “Il faut cultiver notre jardin,” or, we must tend our own garden, has been widely interpreted as a call for disengaging from politics and society—that in order to be at peace about the state of the world, we must tend to our own concerns and not worry about what our neighbors are doing in their own cabbage patches.

But perhaps now you’re also asking yourself, hey, aren’t we supposed to be getting excited about civic responsibility? I promise you, I haven’t forgotten. Because, what Voltaire is talking about in Candide, what Hubbard is talking about in Shantyboat and Payne Hollow, and—in a sense—what Pericles was talking about all those thousands of years ago in his speech about Athenian democracy, is about shifting our understanding of what civic responsibility means for us in action.

What I mean by that is, civic responsibility is not just understanding and participating directly in the democratic experiment through voting and generally upholding law and order—although that is, of course important. Civic responsibility is also the commitment we make to protect and serve our communities through our own individual talents and skills. And in preparation for serving our community, we all must take the time to develop our own love and respect for the places we call home. We must tend our own gardens before we help others tend theirs. Maybe our own beautiful gardens will encourage our neighbors to garden well, themselves.

Harlan was a notoriously private figure, and although he enjoyed writing his books and talking—in small groups or with individuals—about his ideas, he rarely gave public speeches. But a few years ago, while I was researching my biography, I came across a draft of a rare speech he had delivered on April 6, 1972 to a small group of environmental studies students at Indiana University Southeast in New Albany, Indiana—the came city where I now live. The speech, which he called “On the Fringe of Society,” shows that he was working out some of the themes and ideas that would feature in his book about Payne Hollow published a few years later—particularly about the criticism leveled at him over the years for not being more politically engaged as an environmental advocate for the land he claimed to love so much.

Even Wendell Berry—Harlan and Anna’s close personal friend and Harlan’s first biographer—was critical of his lack of interest in protesting or engaging his legislators about the destruction of the river and other natural spaces in Kentucky during the 1950s-1980s. And actually, I want to read you a passage from Berry’s biography of Harlan, which discusses this. Berry writes:

“In the Hubbards’ last years, Public Service Indiana began building a nuclear power plant on the hilltop across the river and a little downstream from Payne Hollow. As the land was condemned and construction began, there was a good deal of protest against the project. […] I wondered, as I am sure other people did, if the Hubbards would take part in the protest. They did not. Harlan acknowledged the intrusion only with a small joke: it was, he said, their castle on the Rhine. Since I was involved in the protest, I wished that they would at least give it their endorsement. I don’t believe they were ever asked to do so, but I was a little disappointed that they did not. The power plant was, after all, a direct and unignorable affront to all that they had done and stood for.

Later I understood that by the life they led Harlan and Anna had opposed the power plant longer than any of us, and not because they had been or ever would be its ‘opponents.’ They were opposed to it because they were opposite to it, because their way of life joined them to everything in the world that was opposite to it. What can be more radically or effectively opposite to a power plant than to live abundantly with no need for electricity? As the power plant rose, demonstrating the wrong way to live in the Ohio Valley, the Hubbards’ life at Payne Hollow quietly went on as before, demonstrating the right way, without bothering to think of itself as demonstration. And then the Marble Hill project collapsed under the burden of technological folly and economic fantasy.

History thus contrived a curious and perhaps fitting emblem to stand at the end of the Hubbards’ life at Payne Hollow. The monstrous wealth and power, whose influence Harlan and Anna had renounced, finally confronted them in their own place. The industrialist’s contempt for any life in any place was balanced across the river by a place and two lives joined together in love. The men of the industrial dream, who served the abstractions of technological ambition, raised their walls above the trees to look down upon a man and woman who served the goodness and beauty of the earth.”

To me, the point of Berry’s story—which is basically a parable—can tell us something valuable about civic responsibility. Some, like Berry, will climb into the trenches and protest, contact legislators and representatives, and agitate in the political sphere. That is their garden. But others, like the Hubbards, will go about protest and community service on a different scale and at a different speed. That is their garden. Both methods, though different, produced similar fruit—and together, both gardens then produced an abundance. In this room, we will have folks that will respond like Berry or like the Hubbards. What is important is that we respond at all. That is civic responsibility.

But back to Harlan’s speech made at IUS in the 1970s. I want to read you some of that speech. Whether or not you are someone who feels a civic duty to care for the environment—although I, personally, hope you all do—I believe it is helpful to see how the Hubbards’ long-term legacy of “non-activist activism” can inspire people to engage civically with their communities.

Harlan said in 1972, seeming to promote both Berry’s and his own way of responding to community needs:

“I feel that I have wandered in here by mistake. I am not a public speaker, speak but little in private for that matter, and you know more about our environmental problems than I do. All that I can give you are a few remarks from my own observation and experience.

I suppose that all of us see that our environment has changed for the worse. Much as I dislike to admit the fact, the earth on which we live is not what it used to be. Nature seems to have lost some of its vitality. I notice with sadness that certain kinds of birds seem to be dwindling, while starlings and blackbirds increase. Some of the wild crops I gather for food are not as abundant as they once were—blackberries, for instance, and good walnuts, are hard to find. In the garden, harmful insects increase, new weeds spread, moles and mice are out of control. Even so, the earth is unbelievably fair, and no man’s life is worthy to be lived on it. But this is not the angle we are concerned with.

The question is, what can you, as an individual, do with effort to bring the earth back to its former purity and cleanliness?

Since this country is still a democracy, public officials respond to the opinions of the people. Work on these public servants, then, from those at the top, down to the local authorities. Join groups dedicated to conservation, like the Wilderness Society and the Sierra Club, to mention only two. Inform yourself of the facts, attend meetings, write letters, sign petitions. Dig up your rose bushes and raise vegetables organically. Get a bicycle, use the automobile as little as possible. Burn candles and oil lamps, dispense with useless electrical gadgets. Shun colored paper towels and use white ones made of recycled paper.

All this will surely bring about some good results, but ultimately the results will be limited and disappointing. Such efforts do not go to the root of the problem. The deterioration of the environment is caused by modern civilization which has turned away from nature. Man thought he could subdue and control nature, and now he has lost Mother Nature’s support and guidance.

Is it possible to return to a natural state in which the earth would be clean and wholesome again? Perhaps the best course would be to pull out of the system and live a life close to the earth. Can this be done?”

Of course, for most of us, the answer is no. Most of us cannot “pull out of the system,” live on the fringe, and eschew the rat race. But Harlan knew that. For me, I think that what we can learn from the example of Harlan and Anna Hubbard, and, both in general and in terms of our civic responsibilities to our community, is pretty simple: we need to fall deeply in love with the place where we live. Only then will we care what happens to it, or to the people living on it with us. It doesn’t matter where that place is—what matters is that we take the time to know it intimately.

This can be literal—falling in love with and, then, protecting the natural landscape and the people it supports. But this can also be more broadly applied to our lives in a place. Civic engagement is not just about government. It is visiting local museums, cultural sites, and libraries. It is learning about your community’s history. It is going out of your way to be neighborly. It is about having tough conversations with people who feel differently than us about certain issues. It is about being open, loving, humble, and authentic.

Authenticity is an important word where Harlan Hubbard is concerned, and I want to close this speech with a very brief reading from my new biography, Driftwood. This comes from the prologue, in which I write:

“I began to understand that the forces that had sculpted the live edges of Harlan’s uncertainty into such smooth, sure beauty were so palpable in an encounter with his life and work that they were capable of transforming us, too.

In part, this comes from Harlan’s incredible authenticity. In the foreword to a reprint of Harlan’s debut book Shantyboat, [Wendell] Berry suggests that this level of authenticity is only possible because ‘Harlan is neither lecturing not prophesying; he makes no such presumption upon our attention or our understanding. He is speaking to us simply because we happen to be listening, which is both discriminating and polite.’ It is the kind of deference to the individuality and intelligence of his reader (or viewer) that, in a recent essay, Jonathan Franzen suggests is absent from most nature writing. ‘Unlike the evangelist who rings doorbells and beatifically declares that he’s been saved,’ Franzen writes, ‘the tonally challenged nature writer can’t see the doors being shut in his face. But the doors are there, and unconverted readers are shutting them.’

One is hard-pressed to find a passage of Harlan’s writing or an example of Harlan’s painting that feels evangelical, or pretentious, or unapproachable. On the contrary, Harlan’s work—which is, like his and Anna’s life, deceptively simple—presents itself like a letter from a friend or a glimpse of a familiar hill. It is personal to Harlan, but it is also personal to us because it is so personal to Harlan. Franzen concludes his essay: ‘Narrative nature writing, at its most effective, places a person (often the author, writing in first person) in some sort of unresolved relationship with the natural world, provides the character with unanswered questions or an unattained goal, and then deploys universally shared emotions—hope, anger, longing, frustration, embarrassment, disappointment—to engage the reader in the journey. If the writing succeeds, it does so indirectly. We can’t make the reader care about nature. All we can do is tell strong stories of people who do care, and hope that caring is contagious.’ The life of Harlan Hubbard is one of these strong stories. I hope, in Driftwood, readers will be able to meet Harlan as I have, through his vibrant life and work, constantly discovering and rediscovering what Thoreau calls ‘the tonic of wildness.’”

Stepping out of the book, here, and tying it back to what we’ve been discussing—I hope that Harlan’s example encourages us to find our own strongest story, our most cared-for garden plot, which can make caring about all sorts of community issues contagious.

Thank you so much for listening.”

Leave a reply to john050c6f4402b Cancel reply