Before you ask, no, I did not build a shanty in the wilderness (although I sure would like to, given the current state of the world).

I have, however, been happily devouring Megan Marshall’s newly published collection of essays, After Lives: On Biography and the Mysteries of the Human Heart, finding her meditations on life writing particularly meaningful having just finished a biography of my own. One of those meditations sent a knowing shiver through me. Marshall writes:

“[Biographers] might have closed the book on their subject, reluctantly or with relief, but the spirit lingers, untethered and tempting: in transcriptions of letters and journals we’d still like to quote stored away in file folders we can’t bear to toss; in inspirational messages tacked to bulletin boards that continue to fire us up; in photos hanging on our office walls that won’t stop staring at us expectantly. The relationship endures, even if we go on to write about someone else.”

Certainly, I hoard hundreds of unused quotes, facts, and anecdotes about Harlan Hubbard that never made it into the manuscript for Driftwood. Some of them drift through my mind unbidden, soon to be banished again (Why didn’t I write more about the cold frame crops? How will anyone forgive me that I didn’t mention Harlan’s beloved copy of Arabian Nights illustrated by Maxfield Parrish? Did I, a cat lover, neglect placing more emphasis on Harlan and Anna’s dogs because I, admittedly, dislike dogs?).

But others truly plague me–especially those born from maddeningly obvious (but so far, unverifiable) connections of the Harlan to other cultural figures and their work.

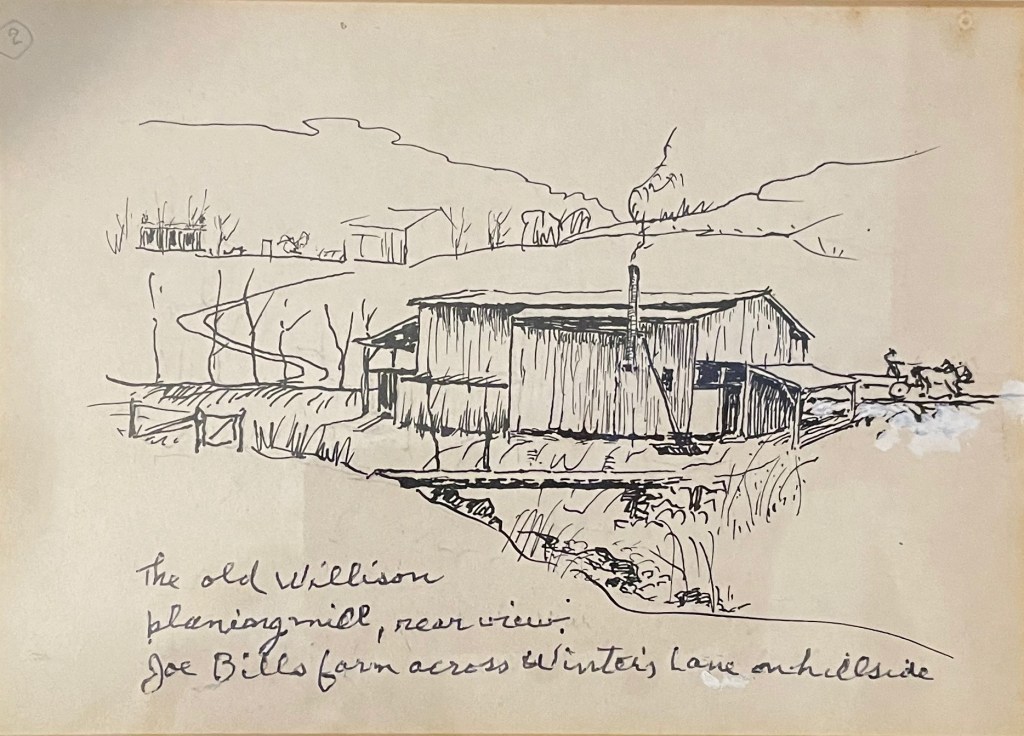

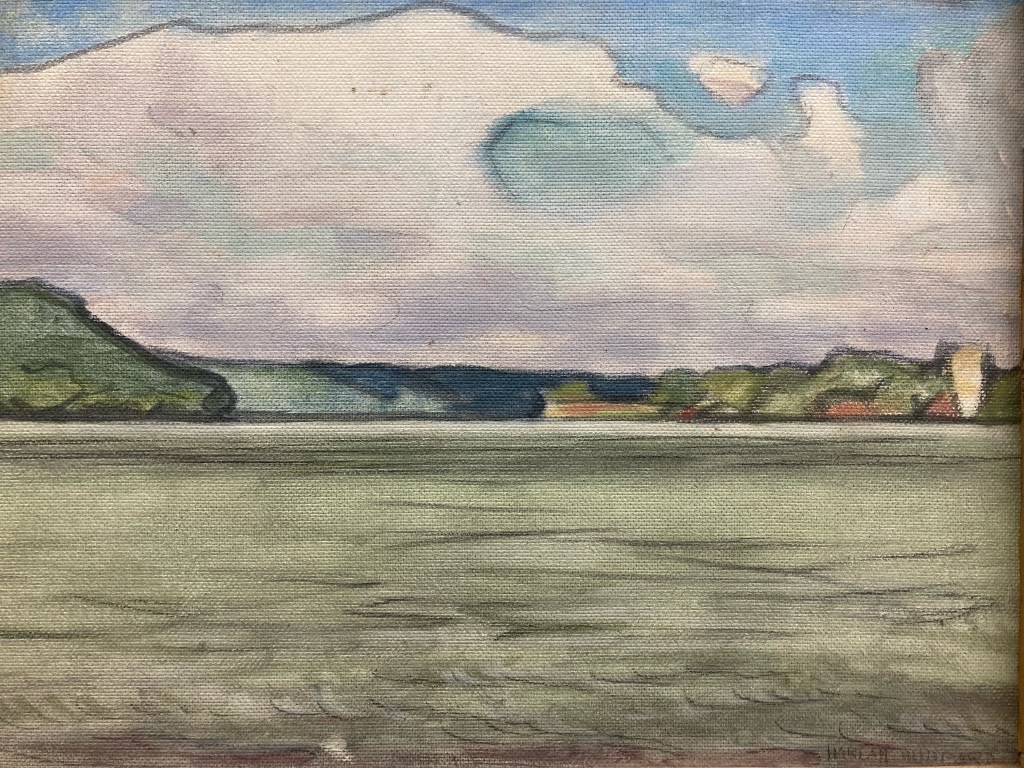

For example. Harlan never mentions the Northern Kentucky landscape painter, Thomas Jefferson “T.J.” Willison anywhere in his books, journals, notes, or correspondence, yet his first painting studio, in an old planing mill in the hills above Brent, belonged to one of Willison’s close relatives. Harlan befriended (and even purchased building supplies from) Cornelius “Neely” Willison and his Brent Frame, Door, and Sash Factory once located on Winter’s Lane.

It seems impossible to me that the subject of a successful landscape painter in the Willison family never came up between Harlan and Neely, but I’ll be damned if I can prove it did. (You can read more about Harlan and the Willison mill in chapter 14 of Driftwood, “The Studio of Nature.”)

Well, another of these nagging mysteries presented itself to me last night as I reached the fifth essay in Marshall’s After Lives. The piece, called “Without,” was not new to me. It had been published before in a remarkable anthology from 2021 edited by Andrew Blauner called Now Comes Good Sailing: Writers Reflect on Henry David Thoreau, which I had consulted often as I researched my biography of Harlan. I remembered reading Marshall’s piece years ago and feeling gobsmacked–yes, gobsmacked!–when she introduced a twelfth-century Japanese poet, monk, and recluse named Kamo no Chōmei and his best-known work Hōjōki (commonly translated to “The Ten-Foot-Square Hut”).

Back in 2021, when I initially read “Without,” I hurriedly sought out a copy of Hōjōki to read for myself. It’s a very brief book, able to be read in a pleasant morning with a single cup of coffee. But its impact over the centuries has been impressive. As Marshall explains, Hōjōki, to Japanese students, is what Henry David Thoreau’s Walden was to many of us: a philosophical call to live more thoughtfully in defiance of a disappointing and often frightening world.

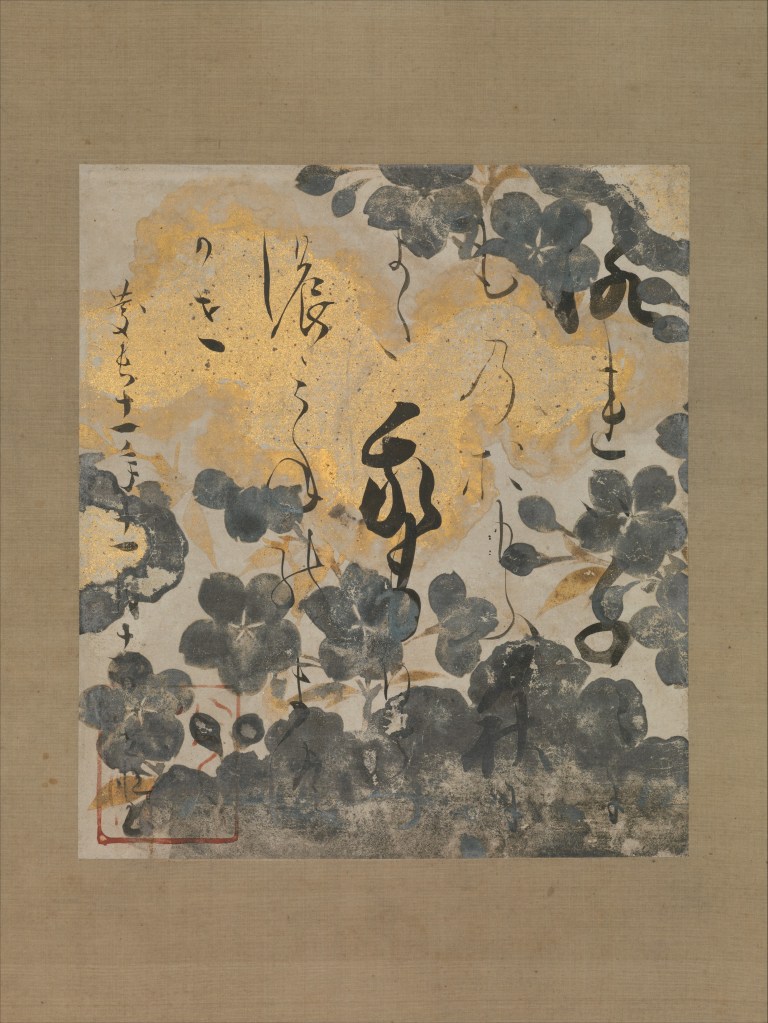

Kamo no Chōmei’s Hōjōki is, if it must be reduced to a single label, an excellent example of Heian era Japan’s interest in sōan bungaku: recluse literature. Chōmei–disaffected with the crumbling political realities of the Heian imperial system and suffering under intense grief from a series of tragic life events–retreated at middle age to a suburb of Kyoto called Fukuwara on the Kamo River. He dedicated himself to the teachings of Buddhism and turned to music and poetry to sustain and enlighten him in his new life.

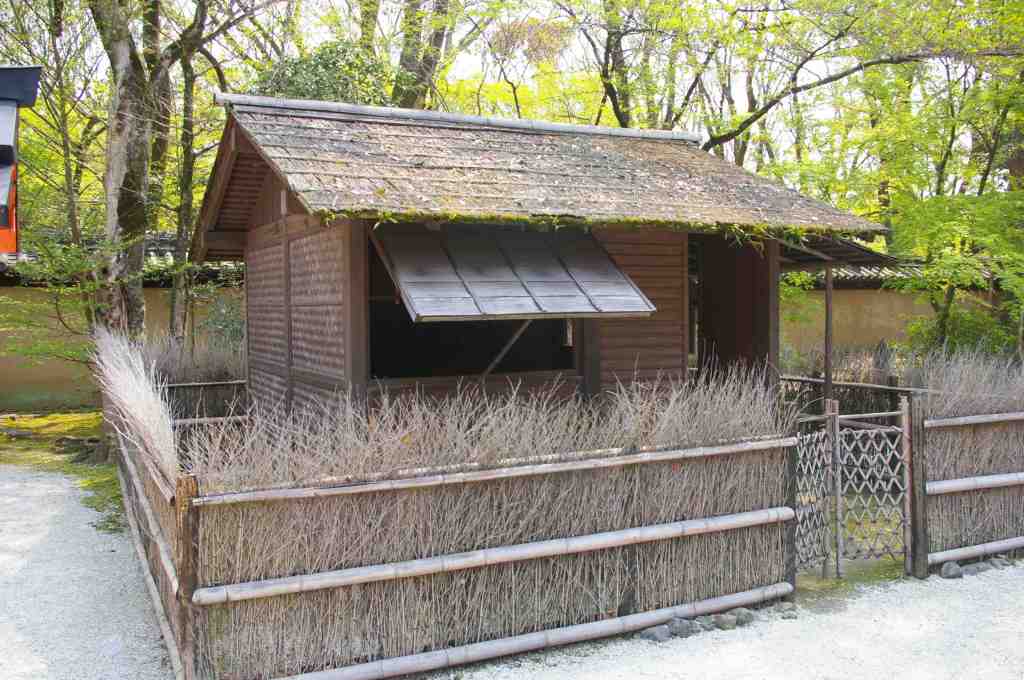

The central part of this new life was the small, ten-foot-square cabin built on the banks of the Kamo. He called it his “passing shelter” or “brief dwelling”–kari no yadori--a reference to the Buddhist ideas of impermanence. Chōmei’s hut was, for him, the answer to his own plaguing question: “Where can one be, what can one do, to find a little safe shelter in this world, and a little peace of mind?”

Of course, for someone like Megan Marshall, who had been steeped in research on the American Transcendentalists for decades as she prepared biographies on the Peabody sisters and Margaret Fuller, Chōmei’s Hōjōki begged for comparison to Walden. In “Without,” Marshall discovers the “Japanese Thoreau” during a colleague’s lecture at Kyoto University and immediately senses those tantalizing, often untraceable threads of biography that connect so many great thinkers over time and space.

She explains that Thoreau would never have read Chōmei, saying, “When Thoreau retreated to Walden Pond in July 1845, he had only recently discovered Buddhism, by way of a translation of the Lotus Sutra done by his transcendentalist colleague Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, working from the French of Eugene Burnouf, published in The Dial under his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson’s editorship–the first English translation of any Buddhist text.”

Nevertheless, when Chōmei writes the following words in Hōjōki, do we not think of Thoreau:

“Small it may be, but there is a bed to sleep on at night, and a place to sit in the daytime. As a simple place to house myself, it lacks nothing. The hermit crab prefers a little shell for his home. He knows what this world holds. The osprey chooses the wild shoreline, and this is because he fears mankind. And I too am the same. Knowing what the world holds and its ways, I desire nothing from it, nor chase after its prizes. My one craving is to be at peace, my one pleasure to live free of troubles.“

Were these not a twelfth-century, Japanese expression of Thoreau’s famous lines:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.”

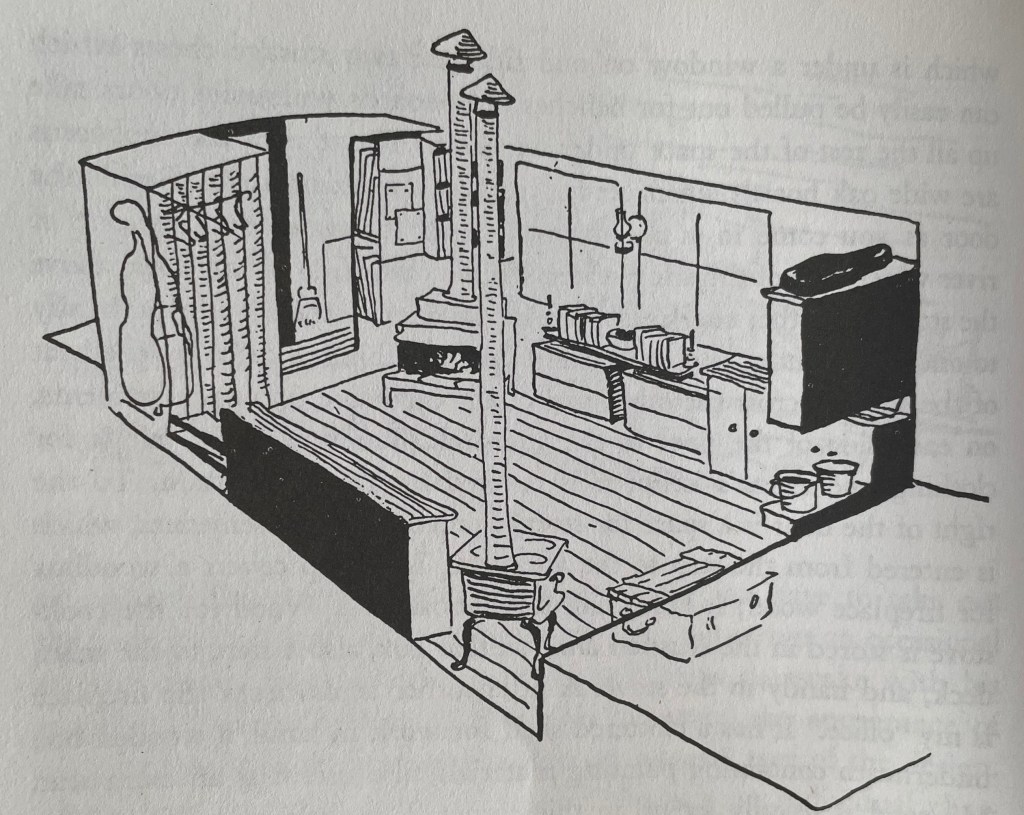

For someone like me, who had spent more than a decade immersed in my own post-Transcendentalist subject, Harlan Hubbard, the Chōmei/Thoreau thread extended to the banks of the Ohio River. Marshall’s essay “Without” had me thinking back to Harlan’s statement made in Payne Hollow (1974), when he describes their shantyboat cabin:

“The boat when completed was a marvel of neatness and comfort. Though bare and without ornament, like a Japanese house, its cabin seemed spacious, having a pair of large, sliding windows on each side and an open fireplace.”

Could it be that Harlan, in addition to idolizing the Thoreauvian experiment at Walden Pond as he did, also knew of Chōmei and his ten-foot-square hut?

Comparisons seemed even more inescapable when I considered the construction and intent behind Harlan’s 1938 studio in Fort Thomas, or the more famous structure he and Anna would build, in 1952, at Payne Hollow in Trimble County, Kentucky. Like Chōmei’s hut, each of these structures was built into a steep hillside and prized the economy of creatively employed space.

Like Marshall with Thoreau, I wanted to do my homework and establish the feasibility of Harlan’s familiarity with the twelfth-century Japanese hermit poet in question. I knew, from my research, that Harlan prized Eastern art and literature from an early age. Exhibitions viewed during his time living in New York City during and immediately after World War I exposed young Harlan to masterworks of Chinese and Japanese painting and design, as well as the overwhelming influence of Japonisme in the work of western artists he admired.

Back in Kentucky, Harlan took violin lessons from the wife of University of Cincinnati scholar Gustav Eckstein who, in the early 1930s, was already publishing important works devoted to Eastern luminaries like Hideyo Noguchi and may have encouraged in Harlan an interest in Japanese culture. Eckstein would later publish a survey on Eastern Art, which undoubtedly included references to one of Harlan’s favorite printmakers, Hiroshige.

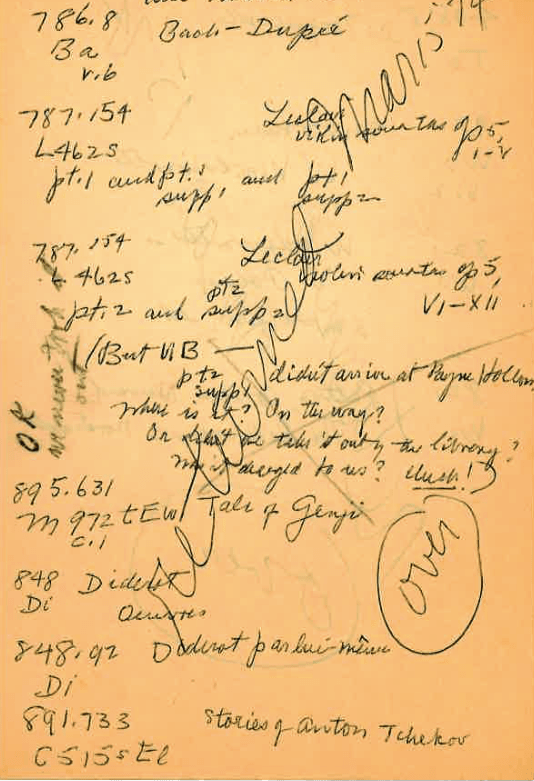

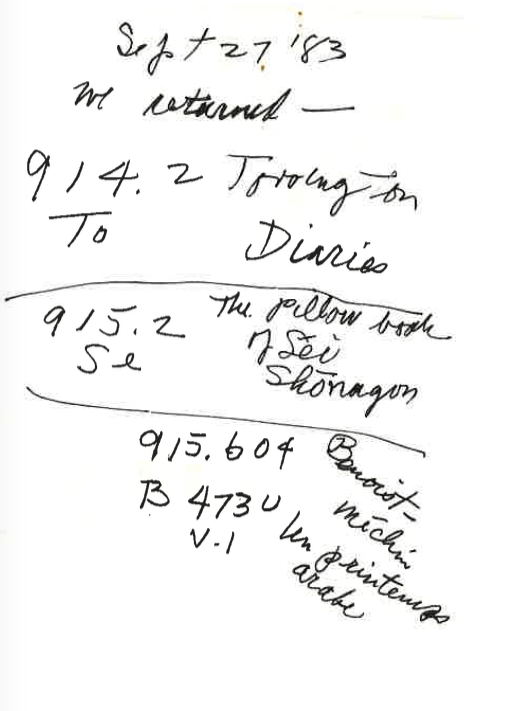

And, of course, I knew from reading the hundreds of meticulously kept library notes made by Anna Hubbard over the course of their marriage (1943-1986) that, together, they had read some of the masterpieces of Heian-era Japan. The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu. The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon. But I have yet to find a mention of Chōmei’s Hōjōki.

Even so, I couldn’t help but hear Harlan’s voice when I read passages from Hōjōki like this:

“I love my tiny hut, my lonely dwelling. When I chance to go down into the capital [Kyoto], I am ashamed of my lowly beggar status, but once back here again I pity those who chase after sordid rewards of the world. If any doubt my words, let them look to the fish and the birds. Fish never tire of water, a state incomprehensible to any but the fish. The bird’s desire for the forest makes sense to none but birds. And so it is with the pleasure of seclusion. Who but one who lives it can understand its joys?”

In the first lines of Hōjōki, Chōmei says, “On flows the river ceaselessly, nor does its water ever stay the same. The bubbles that float upon its pools now disappear, now form anew, but never endure long. And so it is with the people in this world and their dwellings.” It’s not a cheery thought, but it is a relevant one. Chōmei’s book–indeed, his whole experiment, as Thoreau’s–was an acknowledgement of how quickly we can lose everything, including ourselves, if we do not take the trouble to be present and…dare I say…deliberate…about the course of our life. Hōjōki, Walden, and Payne Hollow, even if not linked by literal inspiration, are linked by the concept of ephemerality.

In times like these, when EVERYTHING in life feels vertiginously close to the ephemeral, I return to some essential words in Hubbard’s Payne Hollow that feel especially Chōmei-like in quality and meaning:

“We have lived here twenty years now. Tonight I am considering how to end the book, a problem hard to solve while our life goes on at Payne Hollow in full vigor. Perhaps I shall not write a definitive ending, either of the book or of our occupancy of Payne Hollow. It may be written by a bulldozer swooping down to wipe out this remnant of wilderness in the name of progress, or we might simply drift away with the ever passing river, leaving Payne Hollow to work out its future destiny without us. Some memory of our stay here will possibly remain and we may become a legend of Payne Hollow, distorted by time and repetition. In the distant future someone may relate, if anyone will listen to him, how his grandfather, as a small boy, used to go down into Payne Hollow when it was still a wilderness. There on the riverbank, in a house which they had made out of rocks and trees, lived a couple all by themselves. They planted a garden, kept goats, ate weeds and groundhogs and fish from the river, which in those days was full of fish. They never had to go to the store. The man worked with axe and hoe, without machines. He painted pictures of the old steamboats and made drawings of the life they lived.”

Payne Hollow has since been saved from the bulldozer, but it is still on the front lines of a battle to preserve and protect American wild places. Thoreau’s original cabin no longer stands, and, of course, Chōmei’s ten-foot-square hut has long-since (like, hundreds of years ago) dissolved into its ravine. All were, or are, subject to the kind of entropy that affects us all.

But perhaps what I found comforting about this loose thread connecting Chōmei, Thoreau, and the Hubbards–a thread that, in the folly of an historian, I hold onto tightly and will probably never relinquish from my inquisitive mind–is this: someone, even hundreds of years later from the last, felt inspired to build their own little house in protest to the world’s disappointments.

Perhaps I’ll go build that shanty after all.

Leave a comment